Geostrophic wind | 地轉風

地轉風(Geostrophic wind)

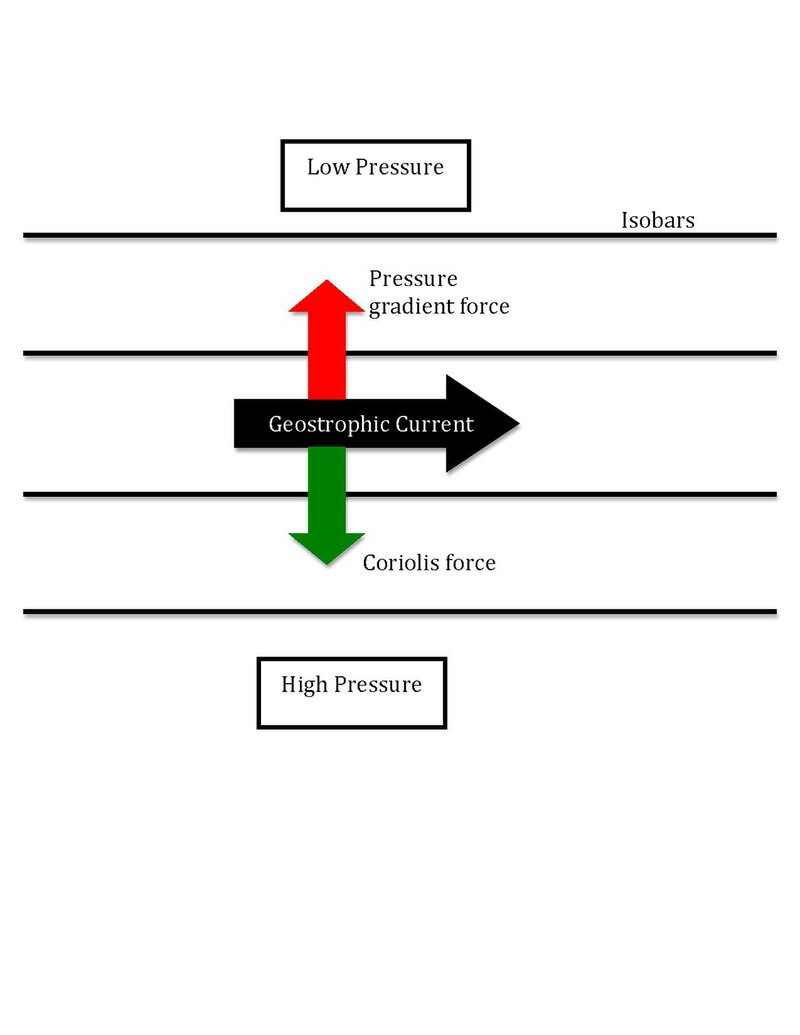

地轉風(Geostrophic wind) 是一種科氏力和氣壓梯度力 (Coriolis force and the pressure gradient force)巧妙平衡下產生的一種理論上的風。這個狀況稱為「地轉平衡」 (geostrophic equilibrium or geostrophic balance)。

- 地轉風的方向和等壓線平行。

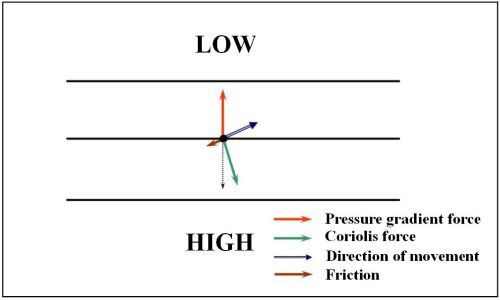

- 這種平衡在自然界中很少出現。真正的風幾乎總是由地面摩擦力等其他力量產生,與地轉風不同。因此,在自然中要實現地轉風只有無摩擦力和等壓線是完美直線的狀況下。

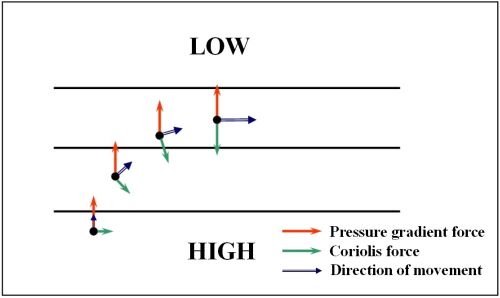

A useful heuristic is to imagine air starting from rest, experiencing a force directed from areas of high pressure toward areas of low pressure, called the pressure gradient force. If the air began to move in response to that force, however, the Coriolis force would deflect it, to the right of the motion in the northern hemisphere or to the left in the southern hemisphere. As the air accelerated, the deflection would increase until the Coriolis force's strength and direction balanced the pressure gradient force, a state called geostrophic balance.

HKO | Geostrophic Wind

Formulation

\[ \begin{align} \frac{\mathrm{D}\boldsymbol{U}}{\mathrm{D}t} = -2\boldsymbol{\Omega} \times \boldsymbol{U} - \frac{1}{\rho} \nabla P + \mathbf{g} + \mathbf{F}_\mathrm{r} \end{align} \] Here \(U\) is the velocity field of the air, \(\Omega\) is the angular velocity vector of the planet, \(\rho\) is the density of the air, \(P\) is the air pressure, \(F_r\) is the friction, \(g\) is the acceleration vector due to gravity and \(\dfrac{D}{Dt}\) is the material derivative.

Why use \(\dfrac{D}{Dt}\) instead of partial derivative? Becuase the veloctiy of air mass can be zero that we move along with this air mass and feel no velocity change, in other words, kinetic energy is conserved. In contrast, partial derivative consider a fixed point in space that velocity of this fixed point can be varied.

Locally this can be expanded in Cartesian coordinates, with a positive \(u\) representing an eastward direction and a positive \(v\) representing a northward direction. Neglecting friction and vertical motion.

\[ \begin{align} \frac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}t} &= -\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial P}{\partial x} + f \cdot v \\[5px] \frac{\mathrm{d}v}{\mathrm{d}t} &= -\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial P}{\partial y} - f \cdot u \\[5px] 0 &= -g -\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial P}{\partial z} \end{align} \]

With \(f = 2 \Omega \sin \phi\) the Coriolis parameter (approximately \(10^{−4} s^{−1}\), varying with latitude).

Assuming geostrophic balance, the system is stationary and the first two equations become:

\[ \begin{align} f \cdot v &= \;\;\,\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial P}{\partial x} \\[5px] f \cdot u &= -\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial P}{\partial y} \end{align} \]

By substituting using the third equation above, we have:

\[ \begin{align} f \cdot v &= -g\frac{\; \frac{\partial P}{\partial x} \;}{\; \frac{\partial P}{\partial z} \;} = g\frac{\partial Z}{\partial x} \\[5px] f \cdot u &= g\frac{\; \frac{\partial P}{\partial y} \;}{\; \frac{\partial P}{\partial z} \;} = -g\frac{\partial Z}{\partial y} \end{align} \]

with \(Z\) the height of the constant pressure surface (geopotential height), satisfying

\[ \frac{\partial P}{\partial x}\mathrm{d}x + \frac{\partial P}{\partial y}\mathrm{d}y + \frac{\partial P}{\partial z}\mathrm{d}Z = 0 \]

This leads us to the following result for the geostrophic wind components \((u_g, v_g)\):

\[ \begin{align} u_\mathrm{g} &= -\frac{g}{f} \frac{\partial Z}{\partial y} \\[5px] v_\mathrm{g} &= \;\;\,\frac{g}{f} \frac{\partial Z}{\partial x} \end{align} \]

The validity of this approximation depends on the local Rossby number. It is invalid at the equator, because \(f\) is equal to zero there, and therefore generally not used in the tropics.

Rossby number

The time, space, and velocity scales are important in determining the importance of the Coriolis force. Whether rotation is important in a system can be determined by its Rossby number, which is the ratio of the velocity, \(U\), of a system to the product of the Coriolis parameter, \(f=2\omega \sin \varphi\), and the length scale, \(L\), of the motion:

\[ Ro = \frac{U}{fL} \]

Hence, it is the ratio of inertial to Coriolis forces; a small Rossby number indicates a system is strongly affected by Coriolis forces, and a large Rossby number indicates a system in which inertial forces dominate. For example, in tornadoes, the Rossby number is large, so in them the Coriolis force is negligible, and balance is between pressure and centrifugal forces. In low-pressure systems the Rossby number is low, as the centrifugal force is negligible; there, the balance is between Coriolis and pressure forces. In oceanic systems the Rossby number is often around 1, with all three forces comparable.

- An atmospheric system moving at U = 10 m/s (22 mph) occupying a spatial distance of L = 1,000 km (621 mi), has a Rossby number of approximately 0.1

- A baseball pitcher may throw the ball at U = 45 m/s (100 mph) for a distance of L = 18.3 m (60 ft). The Rossby number in this case would be 32,000 (at latitude 31°47'46.382").